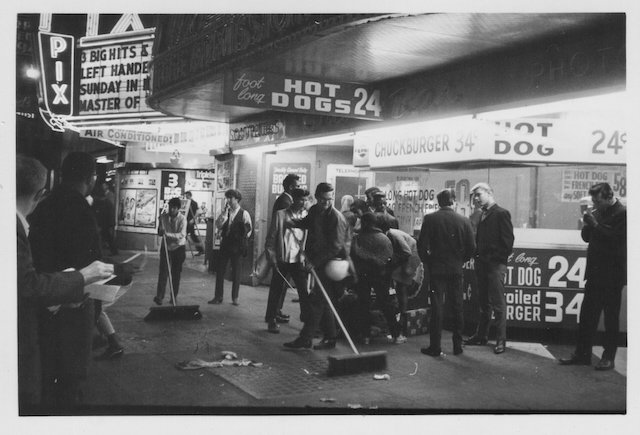

Tracing the history of the downtown lodging house districts where marginally housed youth regularly lived beginning in the late 1800s, I focus on San Francisco’s Tenderloin from the 1950s to the 2010s. Drawing on archival, ethnographic, and oral history research, I explore the social trauma inflicted on street youth and the ways they have worked, collectively and creatively, to reframe and reinterpret those brutal realities. I focus on four world-making practices: kinship networks my informants call “street families,” which resemble the moral economies common among people with severely limited resources; syncretic religious formations I call “street churches,” which are often based on a streetwise, gothic Catholicism; storytelling strategies that enabled youth to secure employment in the district’s vice and bar economies and, at times, to reinterpret the abuse from which they were running; and migratory circuits that connected far-flung tenderloin districts across the country and the people who traversed them, all the while fostering alternative socialities, cooperative economies, and novel forms of mutual aid.

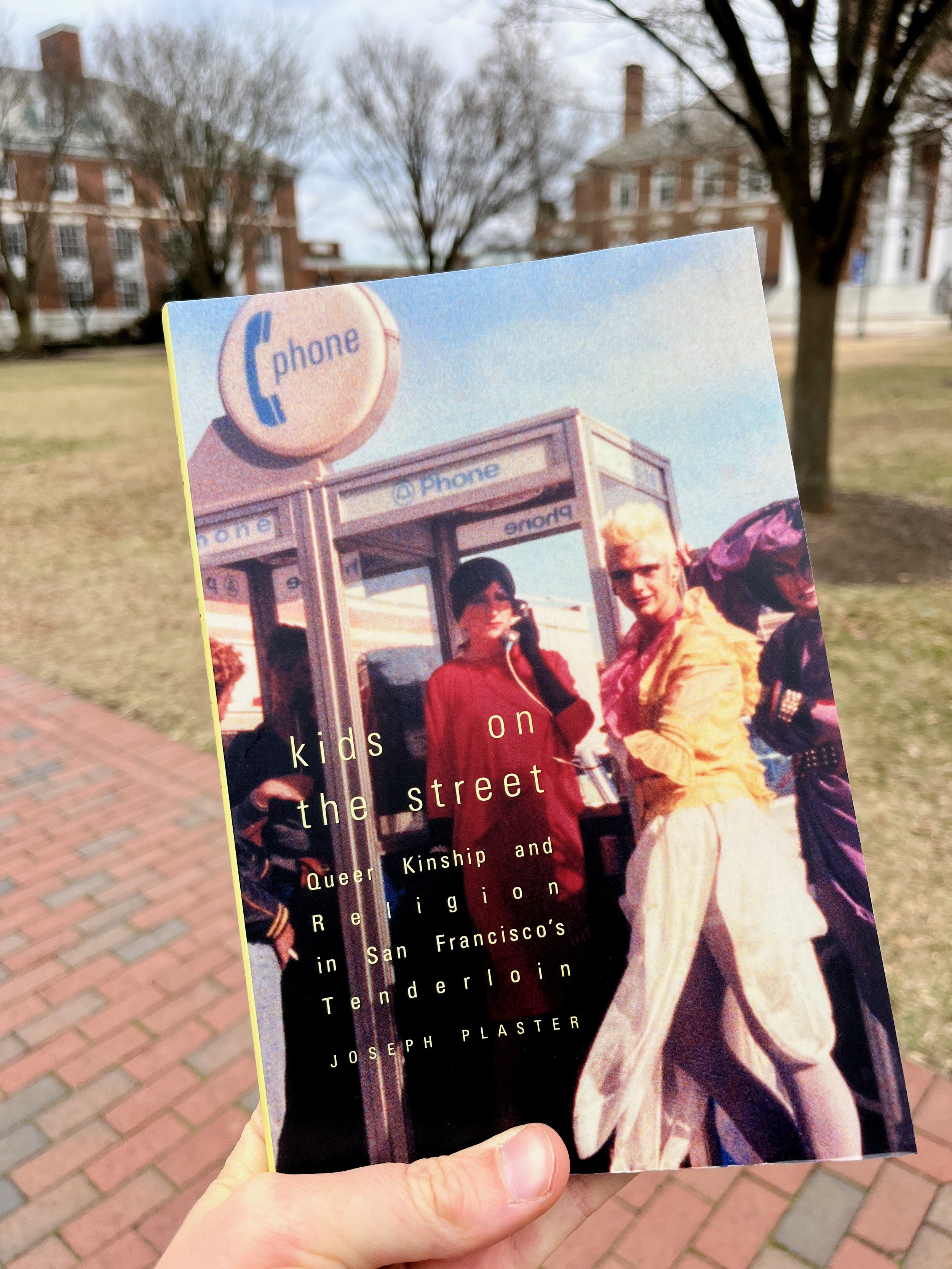

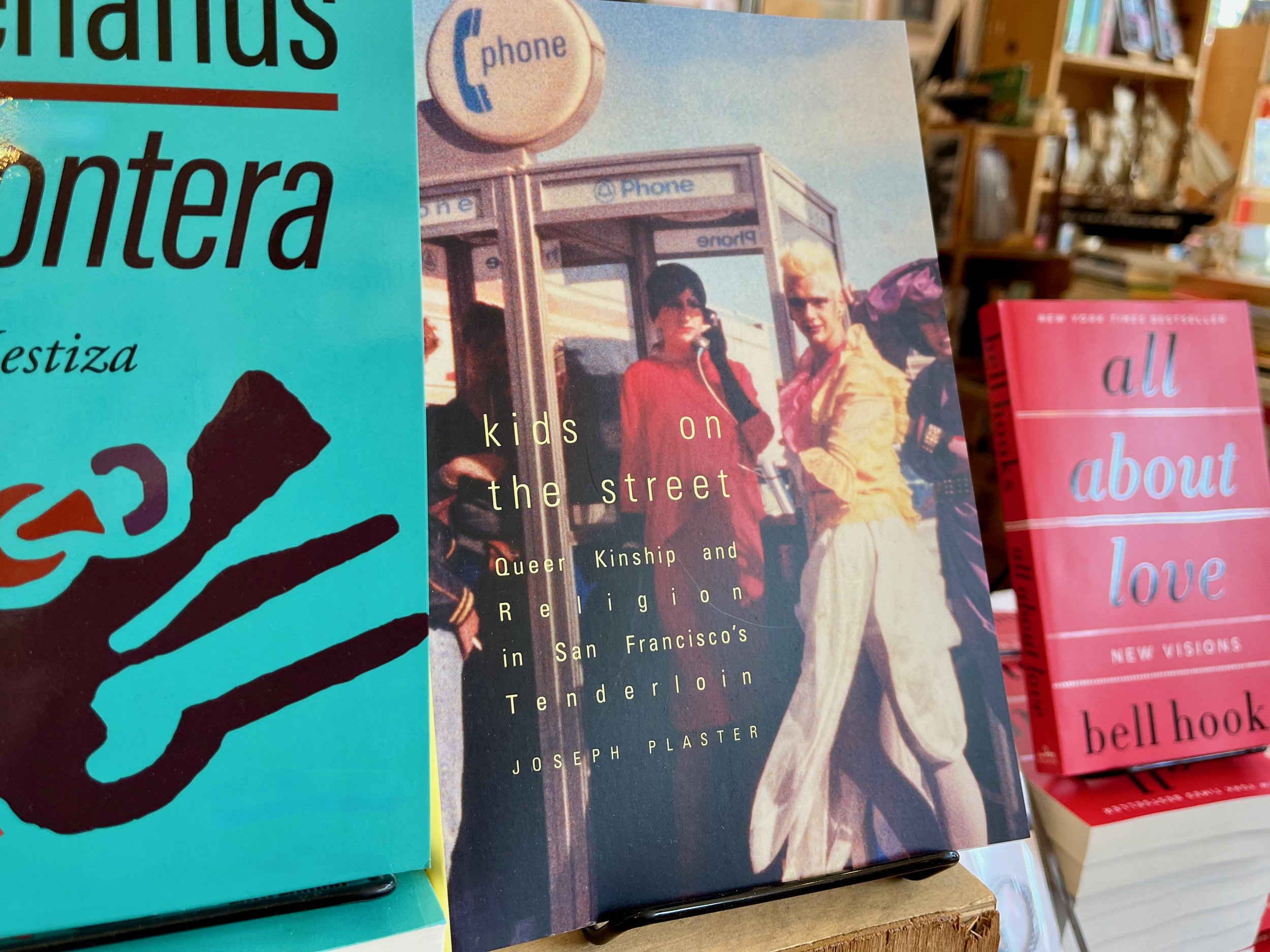

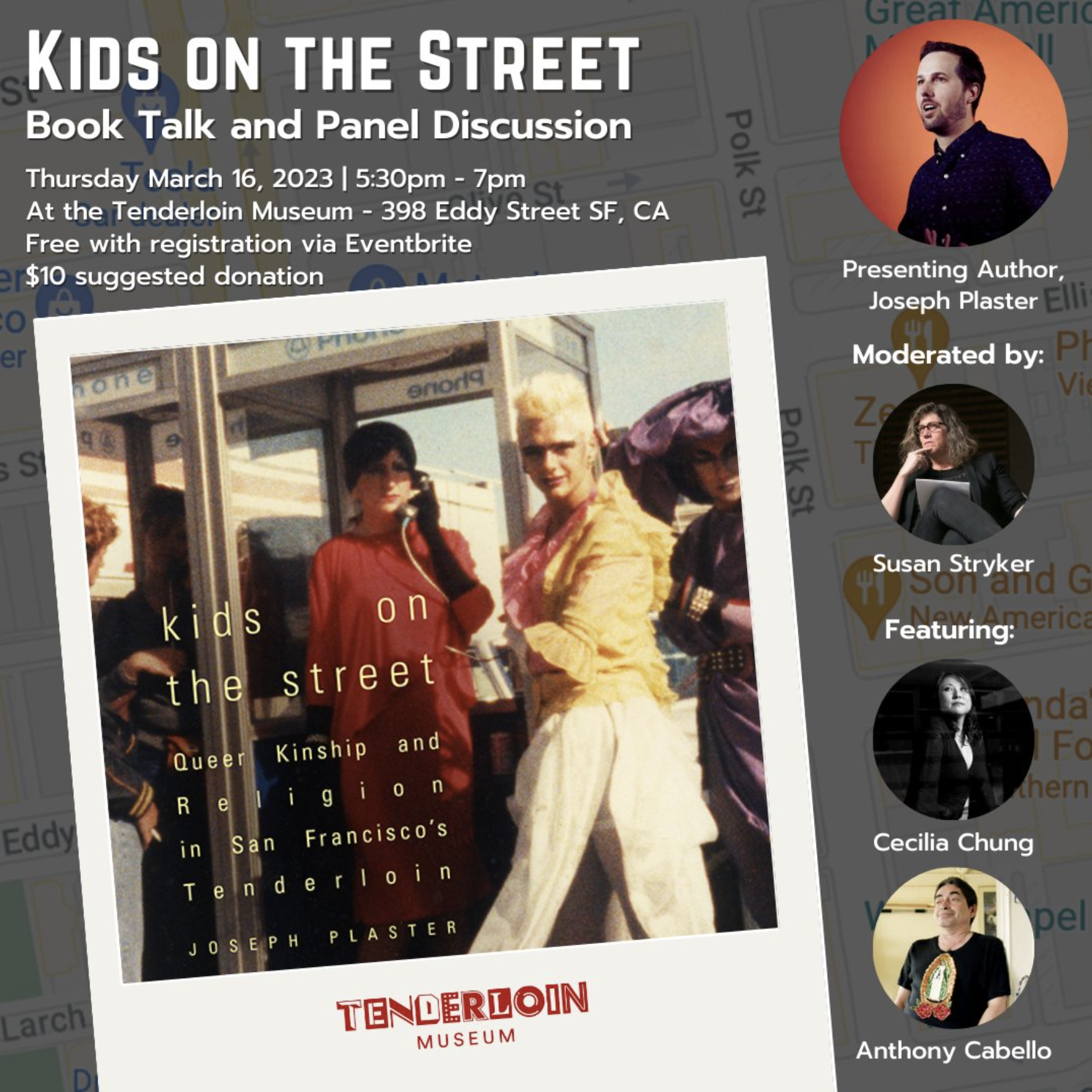

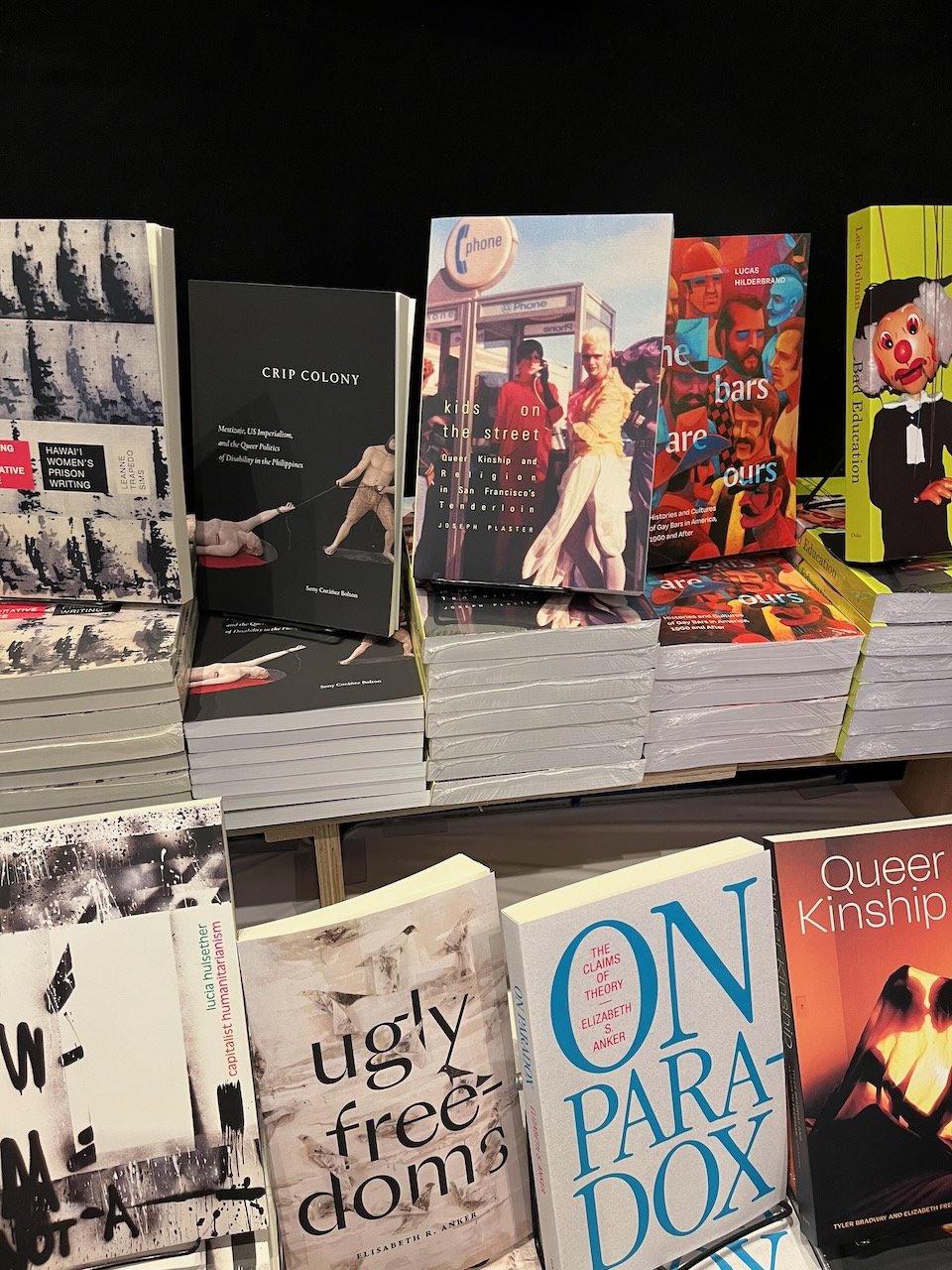

Winner, Randy Shilts Award for Gay Nonfiction, The Publishing Triangle

Winner, Joe William Trotter, Jr. Book Prize for best first book in urban history, Urban History Association

Winner, Oral History Association Book Award

“Kids on the Street is a beautiful, powerful contribution to an inspiring tradition of activist queer and trans public history scholarship. It’s about people marginalized by gender and sexuality finding each other in abjected urban places, sinking down and rising up over and over again, individually and collectively, each time with a promise—partially fulfilled yet never fully realized—of forging new socialities that repair the injustices of the dominant social order. ”

“Representing an innovative approach to queer history, Kids on the Street challenges LGBTQ historiography that often privileges trajectories of community formation and political development that fail to capture the experience of people living in precarious circumstances. Writing with fluidity, beauty, and clarity, Joseph Plaster offers a stunning analysis of the contested processes of memory making and public historical and preservation practices in the context of neoliberal urban development. One of the most exciting and innovative interdisciplinary queer historical works I’ve read recently, this fascinating book makes a major contribution.”

“Plaster writes about street kids with a remarkable amount of generosity and care, and his book offers an exceptional model of ethically engaged, queer historical scholarship. Filled with fresh insights and original archival and ethnographic research, Kids on the Street is an outstanding book, which deserves a wide readership among urban historians, religious studies scholars, historians of childhood, performance studies scholars, and cultural historians of gender nonconformity, race, and sexuality”

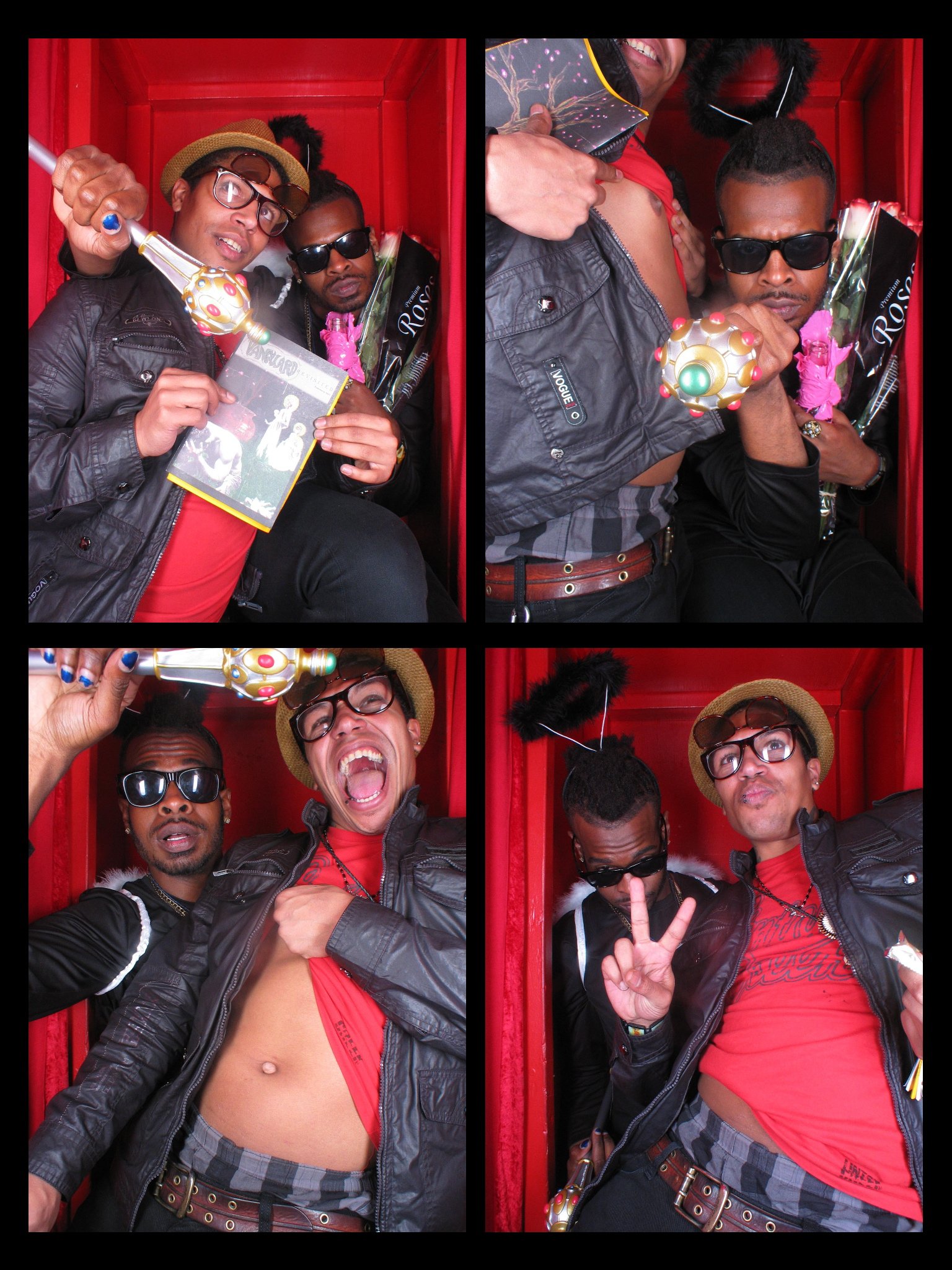

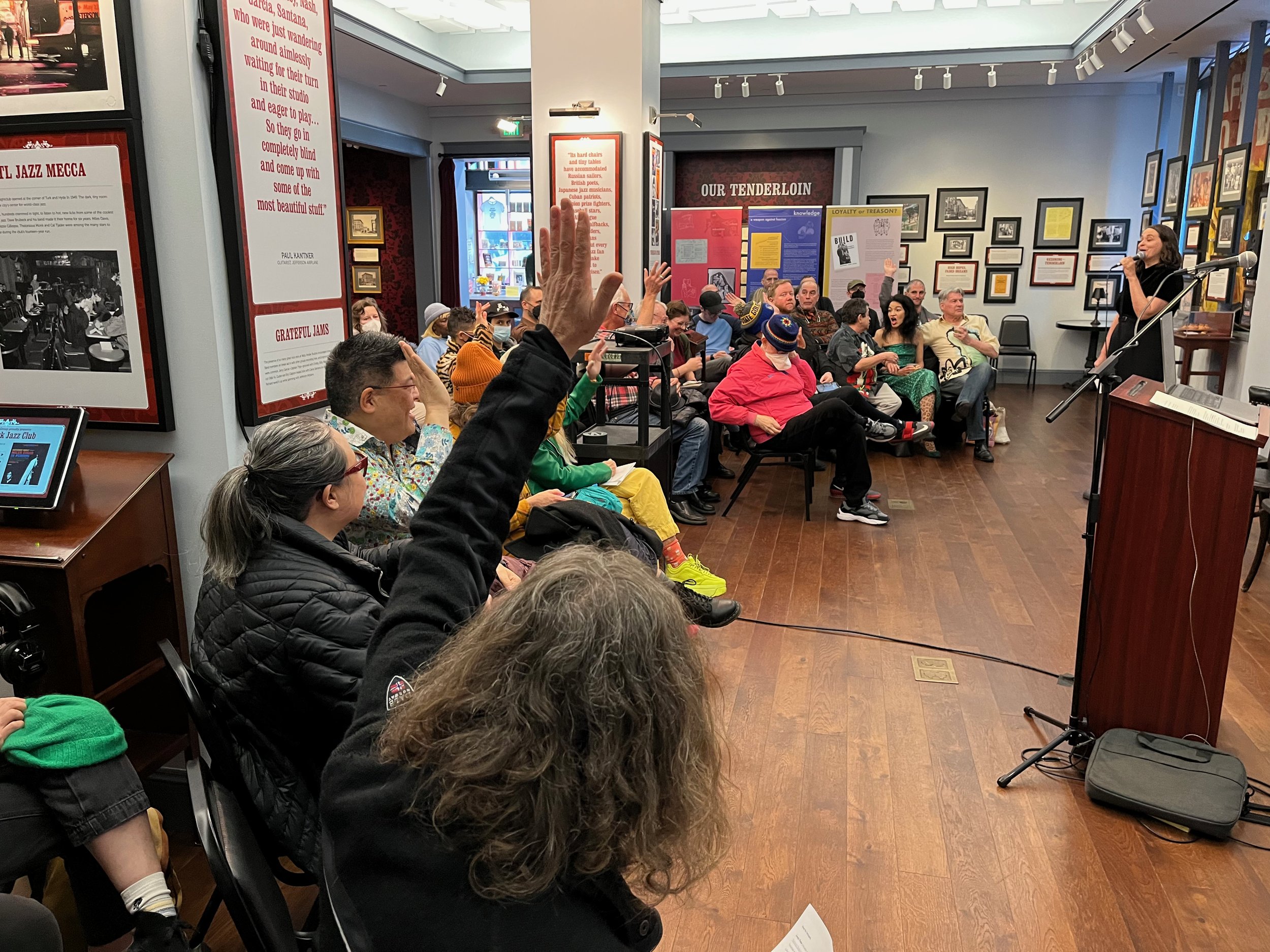

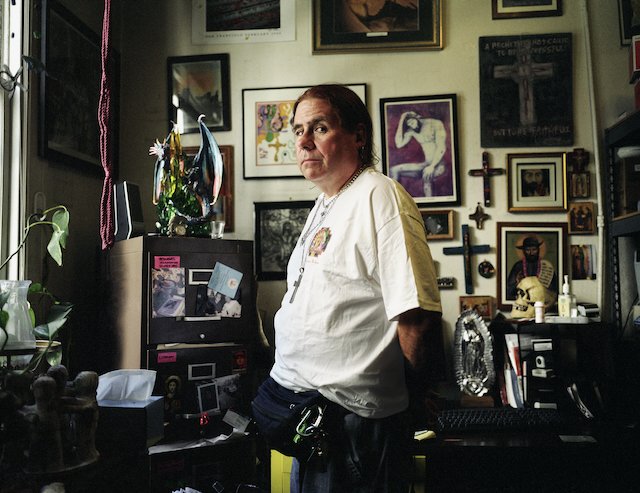

Kids on the Street narrator Alexis Miranda, Imperial Court Empress and former Divas manager

Reviews:

By drawing on ethnographies, archival records, and oral histories Joseph Plaster produces a remarkable portrait of how people within San Francisco’s post-war vice districts metabolized social trauma into queer public cultures, reciprocal exchange, and collective action. The particular brilliance, though, is in its storytelling. This is neither a recovery story of forgotten struggles nor a redemptive narrative of queer liberation. It is about a social world that was both ‘incredibly horrible and wonderful’; of shame and danger, chosen family and mutual aid. Throughout the book, gentrification threatens this social world, but Plaster never allows police raids and redevelopment schemes to displace the main actors in this book. The inclusion of ‘interventions’ offers a model for incorporating public humanities projects into our urban histories, a refreshing mode of storytelling that probes the links between past and present. Kids on the Street is a tour de force, setting a new bar for the craft of writing urban, queer, and public histories.

--Urban History Association book award announcement, 2024

Calling the book “both history and ethnography” does not do justice to its methodological and theoretical innovations. Plaster intricately entwines the historical and the ethnographic by drawing on major works in queer studies, performance studies, and affect theory, as well as by organizing two brilliantly conceived and beautifully narrated public humanities projects…. Plaster’s historical and ethnographic analysis of “street churches,” a longstanding pillar of the kids’ performative economy…makes an invaluable contribution to American religious studies.

-American Religion, Volume 5 Number 2, Spring 2024, pp. 243-252

Plaster highlights the underlying racial bias in the class-oriented discourse of respectability, from the homophile movement of the 1960s to today’s gay assimilationism. His focus on street kids’ participation in the sex economy shows that the seedier pre-gentrification businesses facilitated not only access to jobs in and out of sex work but also a collective sense of self-worth and ways to address and reinterpret the experiences of familial abandonment.

—Guillaume Marche, California History, Volume 101, Issue 3 Fall 2024

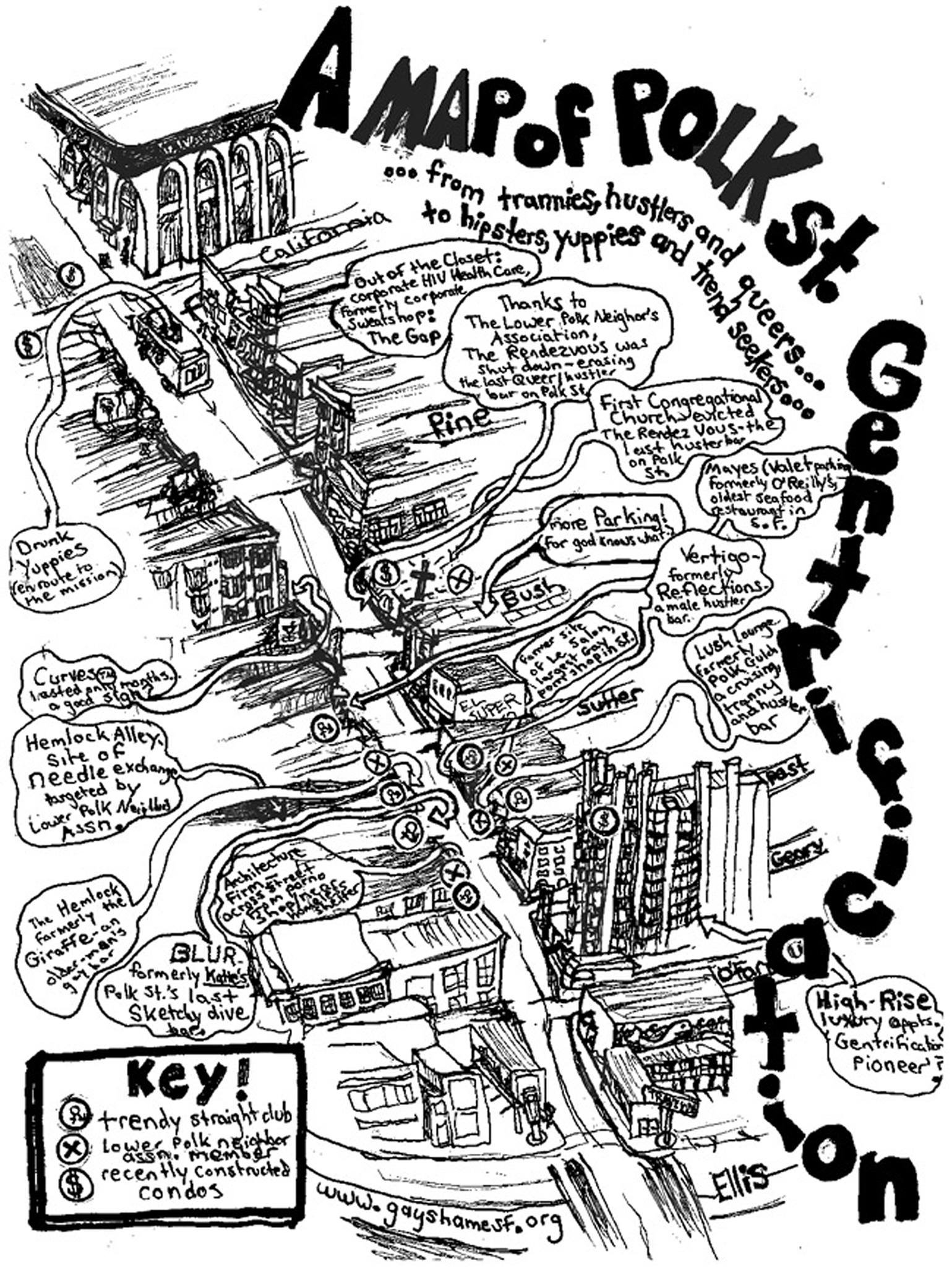

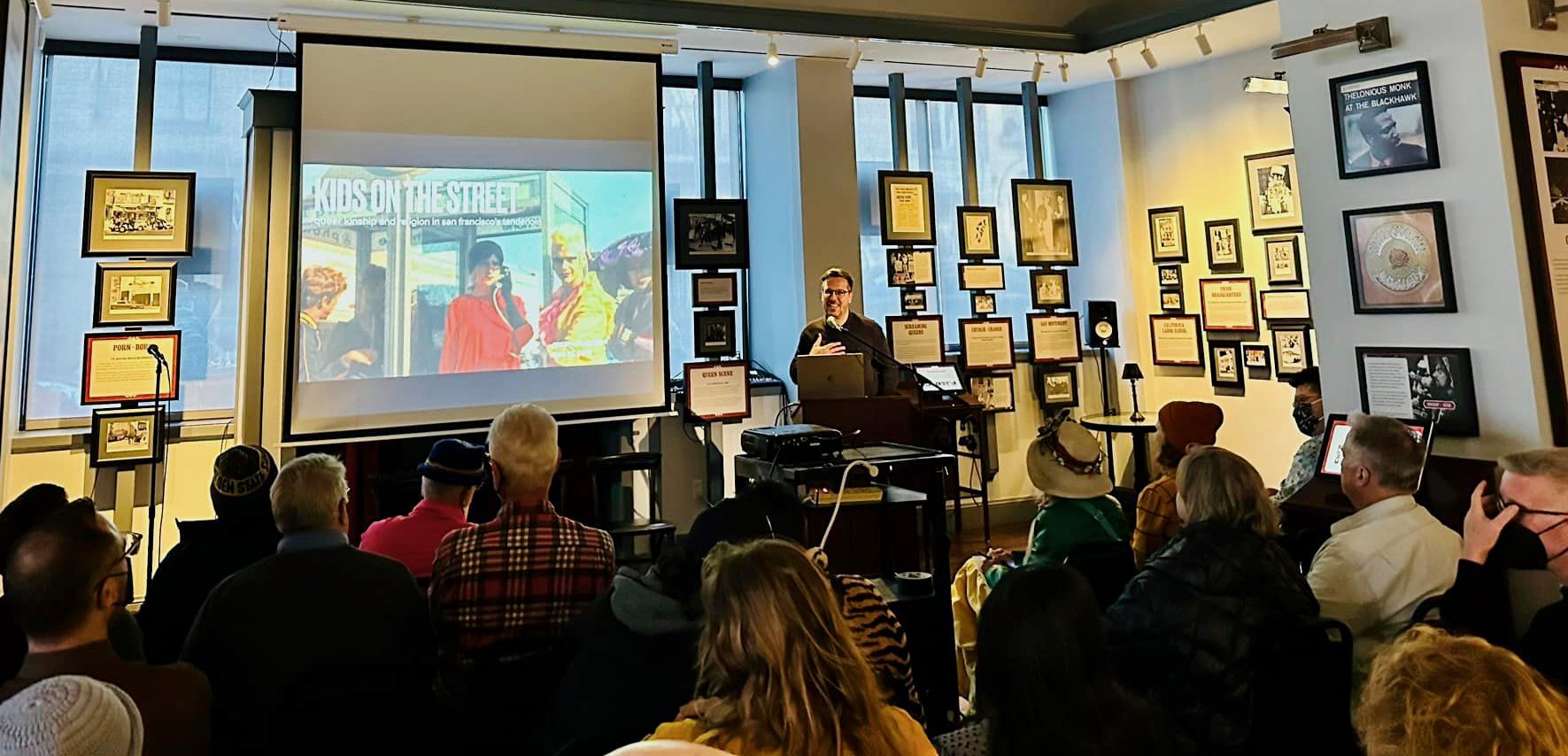

Plaster juxtaposes chapters about the world of street kids with two sections, titled “interventions,” that describe his public history work in the Tenderloin and Polk Street. By including descriptions of these projects in the book and having them “intervene” into his more conventional academic chapters, Plaster emphasizes both the community-based process through which he developed Kids on the Street and its political stakes. Through Kids on the Street and his many years of associated public history work, Plaster seeks to center street kids in queer historical memory—not just in San Francisco (although his commitment to the city is clear), but in broader narratives of queer life.

—The Public Historian, Vol. 46 / February 2024 / No. 1

Kids on the Street is an admirable, thoroughly researched, and carefully documented history of the once vibrant queer culture of the Tenderloin and Polk Street. Featuring scores of interviews with one-time Polk Street denizens, it is also a lament for the displacement of the multiracial, multigender culture of San Francisco’s first post-Stonewall queer district. Drawing attention to that once-thriving, often overlooked culture, the book is a valuable contribution to queer history.

—Gay and Lesbian Review, September 1, 2023

Kids on the Street showcases how performance and movement itself, religious practices and a culture of mutual aid helped people overcome a variety of social traumas …This is an exceptionally well-researched book that uplifts marginalized voices and perspectives with profound implications which transcend disciplinary boundaries. [It] is essential reading for historians of twentieth-century California, youth, urban development, and queer history at the very least.

—European Journal of American Culture, Volume 42 Numbers 2 & 3, 2023

In an era when gentrification, the racist and classist demonization of unhoused people, and anti-trans statecraft threaten the livelihoods of far too many young people, Kids on The Street offers essential context for these disturbing developments. More importantly, Kids on The Street treats abused and abandoned youth not as one-dimensional victims, but as complex historical actors with something meaningful to say about a violent world that spectacularly failed them…His book offers an exceptional model of ethically engaged, queer historical scholarship.

— The Urban History Association blog, April 2024

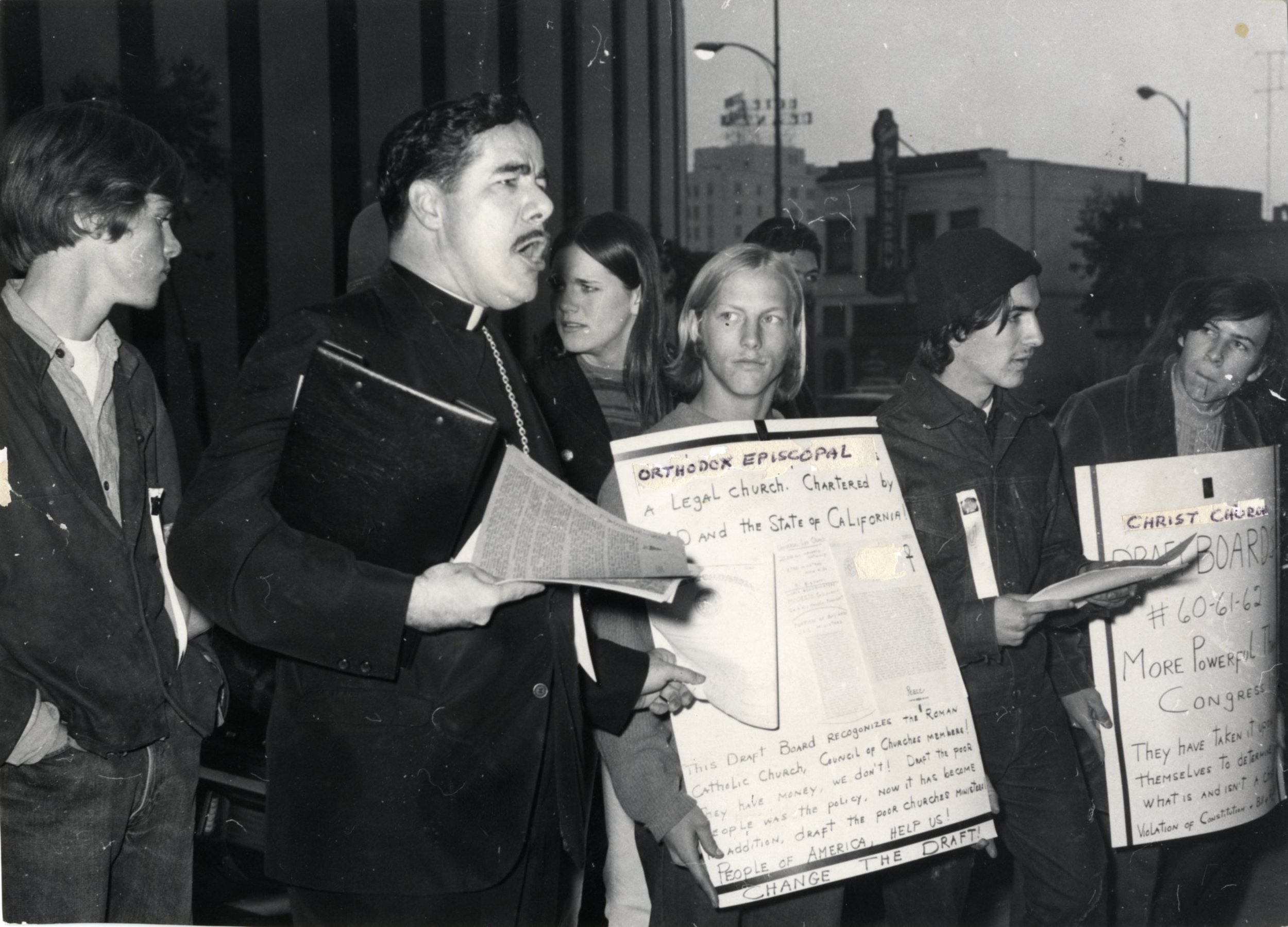

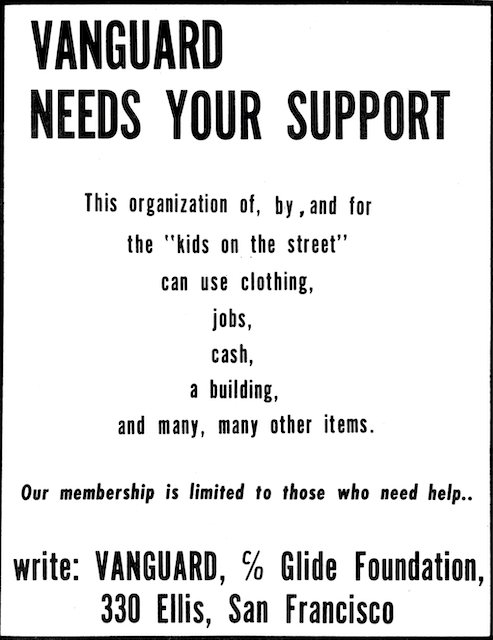

[Kids on the Street] show[s] the remarkable resilience of poor and housing-unstable queer family—a 'moral economy of reciprocity' as the book puts it—that has held strong in San Francisco's Tenderloin and other 'tenderloin' zones throughout the country, and which has 'been overshadowed by major narratives of gay progress and pride.' Along the way, and through dozens of fascinating interviews, we get colorful histories of organizations like Vanguard...and indelible characters like Reverend River Sims, the 'punk priest of Polk Street.

—48 Hills, March 15, 2023

Kids on the Street looks beyond the popular queer historical focus on progress and pride and tells a grittier and more sophisticated story. Experiences of abuse, loss, shame, resilience, and resistance come to the surface. San Francisco’s streets have been dangerous and alienating in many ways, the site of violence and police brutality, but they also gave rise to “street families” (75) and tight-knit groups of friends.

—The Journal of the History of Childhood and Youth, Volume 17, Number 3, Fall 2024